In Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis, the terms “symptom” and “sinthome” have meanings that differ from their use in medicine.

Symptom (Symptôme):

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, a symptom is not merely a sign of illness but rather a form of unconscious expression. Lacan views the symptom as a symbolic act that encompasses not only physical or psychological manifestations but also that which resists symbolization. It may represent the way in which the subject copes with what cannot be articulated in words. For Lacan, the symptom is often linked to what he calls the “Real” – that which cannot be fully integrated into the symbolic order of language. Symptoms can serve as a means of bypassing or masking unconscious conflicts or desires.

Sinthome (Sinthome):

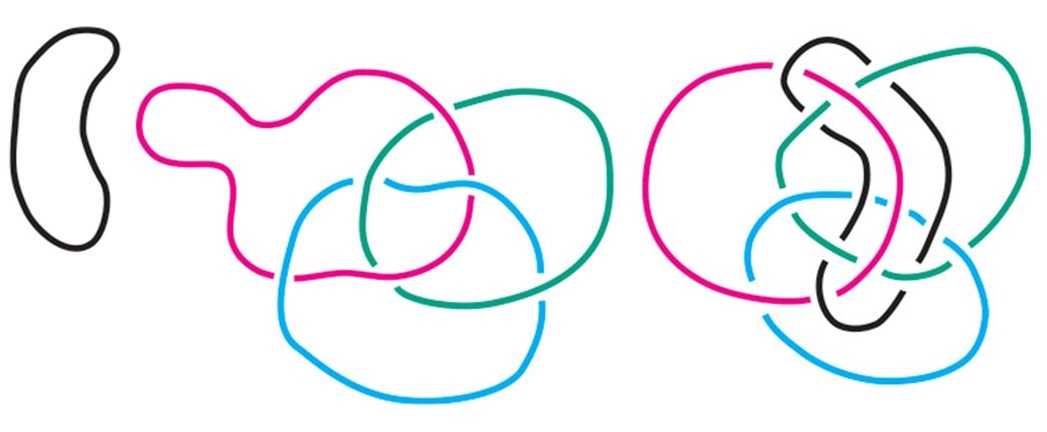

Lacan introduced the terms “symptom” and “sinthome” in the later period of his career, beginning with his 1975-1976 seminar, known as “Seminar XXIII: The Sinthome.” “Sinthome” is a neologism Lacan uses to describe the symptom in its purest form – something that is an intrinsic part of the subject, which not only symbolizes but also literally holds the psyche together. The sinthome is not simply a sign of disorder but rather a structure that ensures the subject’s unity, even if this unity is problematic. In this sense, the sinthome can be seen as a positive aspect of symptomatology, where symptoms do not merely indicate a problem but resolve it, forming the subject’s unique structure.

Thus, in Lacan’s work, “symptom” and “sinthome” share both common and distinct characteristics, with the sinthome emphasizing the structural role of the symptom in the psychic life of the individual.

Ideal Ego (Ideal du Moi) and Ego Ideal (Moi Idéal)

Leave A Comment